Hosting a website on a Raspberry Pi with IPv6 and SSL (part 1)

Our hosted Raspberry Pi 3 servers make a great platform for learning how to run a server. They’re particularly interesting as they only have IPv6 connectivity, yet they can still be used very easily to host a website that’s visible to the whole Internet. This guide walks through the process of setting up a website on one of our hosted Pis, including hosting your own domain name, setting up an SSL certificate from Let’s Encrypt, automating certificate renewal, and using our IPv4 to IPv6 HTTP reverse proxy.

Get a Raspberry Pi

First, get yourself a hosted Raspberry Pi server. You can order these from our website, and be up and running in two minutes:

Click on the link to configure your server and you’ll be shown details of your server, and prompted to configure an SSH key:

We use SSH keys rather than passwords. Click on the link, and you’ll be asked to paste in an SSH public key. If you don’t have an SSH public key, you’ll need to generate one. On Unix you can use ssh-keygen and on Windows you can use PuTTYgen. Details of exactly how to do this are beyond this guide, but Google will throw up plenty of other guides.

Connect to your server

Once done, you’re ready to SSH to your server. If you’ve got an IPv6 connection, you can connect directly. The Pi used for this walkthrough is called “mywebsite”, so where you see that in these instructions, use whatever name you chose for your server. To SSH directly, connect directly to mywebsite.hostedpi.com. Sadly, the majority of users currently only have IPv4 connectivity, which means you’ll need to use our gateway box. Your server page will give you details of the port you need to connect to. In my case, it’s 5125:

$ ssh -p 5125 root@ssh.mywebsite.hostedpi.com

The authenticity of host '[ssh.mywebsite.hostedpi.com]:5125 ([93.93.134.53]:5125)' can't be established.

ECDSA key fingerprint is SHA256:Hf/WDZdAn9n1gpdWQBtjRyd8zykceU1EfqaQmvUGiVY.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)? yes

Warning: Permanently added '[ssh.mywebsite.hostedpi.com]:5125,[93.93.134.53]:5125' (ECDSA) to the list of known hosts.

The programs included with the Debian GNU/Linux system are free software;

the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the

individual files in /usr/share/doc/*/copyright.

Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent

permitted by applicable law.

Last login: Fri Nov 4 14:49:20 2016 from 2a02:390:748e:3:82cd:6992:3629:2f50

root@raspberrypi:~#

You’re in!

Install a web server

We’re going to use the Apache web server, which you can install with the following commands:

apt-get update

apt-get install apache2And upload some content:

scp -P 5125 * root@ssh.mywebsite.hostedpi.com:/var/www/html/Now, visit http://www.yourserver.hostedpi.com in your browser, and you should see something like this:

Another computer on the web serving cat pictures!

Host your own domain name

Magically, this site on your IPv6-only Raspberry Pi 3 is accessible even to IPv4-only users. To understand how that magic works, we’ll now host a different domain name on the Pi. We going to use the name mywebsite.uid0.com.

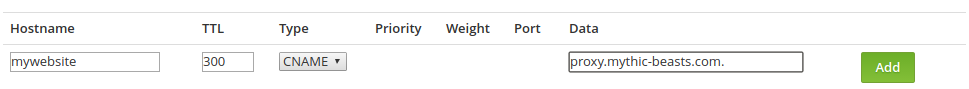

First, we need to set up the DNS for this hostname, but rather than pointing it directly at our server, we going to direct it at our IPv4 to IPv6 HTTP proxy, by creating a CNAME to proxy.mythic-beasts.com:

If you’re using a hostname that already has other records, such as a bare domain name that already has MX and NS records, you can use an ANAME pseudo-record.

Our proxy server listens for HTTP and HTTPS requests on both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses, and then uses information in the request header to determine which server to direct it to. This allows us to share one IPv4 address between many IPv6-only servers (actually, it’s two IPv4 addresses as we’ve got a pair of proxy servers in different data centres).

We need to tell the proxy server where to send requests for our hostname. To do this, visit the IPv4 to IPv6 Proxy page the control panel. The endpoint address is the IP address of your server, which you can find on the details page for your server, as shown above.

For the moment, leave PROXY protocol disabled – we’ll explain that shortly. After adding the proxy configuration, wait a few minutes, and after no more than five, you should be able to access the website using the hostname set above.

Enable HTTPS

We’re firmly of the view that secure connections should be the norm for websites, and now that Let’s Encrypt provide free SSL certificates, there’s really no excuse not to.

We’re going to use the dehydrated client, as it’s packaged for the Debian operating system that Raspbian is based on. Unfortunately, it’s not yet in the standard Raspian distribution, so in order to get it, you’ll need to use the “backports” repository.

To do this, first add the backports package repository to your apt configuration:

echo 'deb http://httpredir.debian.org/debian jessie-backports main contrib non-free' > /etc/apt/sources.list.d/jessie-backports.listThen add the keys that these packages are signed with:

apt-key adv --keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com --recv-keys 7638D0442B90D010

apt-key adv --keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com --recv-keys 8B48AD6246925553Now update your local package list, and install dehydrated:

apt-get update

apt-get install dehydrated-apache2We need to configure dehydrated to tell it which hostnames we want certificates for, which we do by putting the names in /etc/dehydrated/domains.txt:

echo "mywebsite.uid0.com" > /etc/dehydrated/domains.txtIt’s also worth setting the email address in the certificate so that you get an email if the automatic renewal that we’re going to setup fails for any reason, and the certificate is close to expiry:

echo "CONTACT_EMAIL=devnull@example.com" > /etc/dehydrated/conf.d/mail.shNow we’re ready to issue a certificate, which we do by running dehydrated -c. This will generate the necessary private key for the server, and then ask Let’s Encrypt to issue a certificate. Let’s Encrypt will issue us with a challenge: a file that we have to put on our website that Let’s Encrypt can then check for. dehydrated automates this all for us:

root@raspberrypi:~# dehydrated -c

# INFO: Using main config file /etc/dehydrated/config

# INFO: Using additional config file /etc/dehydrated/conf.d/mail.sh

Processing mywebsite.uid0.com

+ Signing domains...

+ Generating private key...

+ Generating signing request...

+ Requesting challenge for mywebsite.uid0.com...

+ Responding to challenge for mywebsite.uid0.com...

+ Challenge is valid!

+ Requesting certificate...

+ Checking certificate...

+ Done!

+ Creating fullchain.pem...

+ Done!

We now need to configure Apache for HTTPS hosting, and tell it about our certificates. First, enable the SSL module:

a2enmod sslNow add a section for an SSL enabled server running on port 443. You’ll need to amend the certificate paths to match your hostname. You can copy and paste the block below straight into your terminal, or you can edit the 000-default.conf file using your preferred text editor.

cat >> /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/000-default.conf <<EOF

<VirtualHost *:443>

ServerAdmin webmaster@mywebsite.hostedpi.com

DocumentRoot /var/www/html

ErrorLog ${APACHE_LOG_DIR}/error.log

CustomLog ${APACHE_LOG_DIR}/access.log combined

SSLEngine On

SSLCertificateFile /var/lib/dehydrated/certs/mywebsite.uid0.com/fullchain.pem

SSLCertificateKeyFile /var/lib/dehydrated/certs/mywebsite.uid0.com/privkey.pem

</VirtualHost>

EOF

Now restart Apache:

systemctl reload apache2and you should have an HTTPS website running on your Pi:

Automating certificate renewal

Let’s Encrypt certificates are only valid for three months. This isn’t really a problem, because we can easily automate renewal by running dehydrated in a cron job. To do this, we simply create a file in the directory /etc/cron.daily/:

cat > /etc/cron.daily/dehydrated <<EOF

#!/bin/sh

exec /usr/bin/dehydrated -c >/var/log/dehydrated-cron.log 2>&1

EOF

chmod 0755 /etc/cron.daily/dehydrated

dehydrated will check the age of the certificate daily, and if it’s within 30 days of expiry, will request a new one, logging to /var/log/dehydrated-cron.log.

Rotate your log files!

When setting up a log file, it’s always good practice to also set up log rotation, so that it can’t grow indefinitely (failure to do this has cost one of our founders a number of beers due to servers running out of diskspace). To do this, we drop a file into /etc/logrotate.d/:

cat > /etc/logrotate.d/dehydrated <<EOF

/var/log/dehydrated-cron.log

{

rotate 12

monthly

missingok

notifempty

delaycompress

compress

}

EOF

Client IP addresses

If you look at your web server log files, you’ll see one disadvantage of using our proxy to expose your site to the IPv4 world: all requests appear to come from our proxy servers, rather than the actual clients. This is obviously a bit annoying for log file analysis, but is a big problem for any kind of IP-based access controls or rate limiting. Fortunately, there’s a solution, which we’ll look at in the next post.